All that glitters: a year in London

It is strange that the first post I wrote about London was during my first week and the second one I am writing is during my last week here, and I doubt it will be completed even after I have returned to Delhi. It is perhaps best I should start with a description of the street I lived on, if only to get my writer’s block out-of-the-way.

I: Room with a view

The street where I lived was quite utilitarian, with little thought paid to aesthetics. My room being that of a student accommodation had a window that could not be opened. All I had was a glass window that sometimes doubled up as a weather forecaster if my phone was kept away (or dead). Windows across all student accommodations in UK are sealed to prevent student suicides.

I could see a railway line running in front of my window, and during my initial days when I knew no one, watching trains go by gave me great pleasure. The wall that ran along the railway line was littered with graffiti. I distinctly remember one that said ‘Tories Loot’. Another one went ‘Billions to banks’, left the phrase incomplete, only to complete it with ‘never again’ after about ten feet. Walls along railway lines in India are seldom ventilators for such frustration and more often than not advertisements for anything that did not get a slot on the television: maths classes or quack doctors. Also, unlike trains in India where you can see people sitting inside (and they at you), trains that ran in the UK had an uptight air about them. Their windows were sealed too, and tinted. Privacy is of utmost importance in the West.

If I craned my neck until I could no more, I could see a Tesco to my left. Every Friday, a car would stop by the crossing outside my hostel with ‘Sultans of Swing’ blaring out. Beyond the railway lines was another student accommodation. If the Sun was good, then I could make out study tables and white curtains. Sometimes at night they lit up their staircase, and I could see that as well. But I do not recall seeing a single soul inside. The railway line proceeded on to a bridge and then disappeared behind a shock of trees, which was beyond my window’s field of view. The bridge arched over Holloway Road and rattled insanely each time a train ran over it, but you’d have to stand under the bridge to hear the noise. A footpath ran across the length of Holloway Road, but the stretch under the bridge sheltered more homeless people than the rest of the street.

Construction went on in full swing throughout my stay there, and within another six months another building had stood up obscuring my railway lines and graffiti. But it only gave me more avenues to ogle. The makeshift cabin that the construction workers used had its own window from which I could see them eating or reading, although I could only see their hands and not their. Bulldozers and cranes operated freely on the site, often as if at free-will. Every morning, the feeble British Sun would stream in my window and I would wake up to the automated horn of the bulldozer that went ‘stay clear, this vehicle is turning right’. To me it always sounded: ‘stay clear, this vehicle is burning bright’.

Holloway Road was little more than an assortment of supermarkets, although ancient patrons of the road will disagree. Nonetheless, the street gave me very good practice for honing one’s skills as a flaneur. These supermarkets catered to a different variety of people. Sainsbury’s and Tesco catered to a crowd I could relate to. Waitrose spared no effort in making it clear it was cut above the rest. There was something about Waitrose that was distinctly British, be it the exotic breed of dogs that its patrons tied outside or the line of Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph as one entered its precincts. So, when someone told me later on that there is a Waitrose outlet wherever there is British diaspora in any country, I was not surprised. The people who frequented or worked at Waitrose were all very clean-cut British people with cut-glass accents and spoke in a way distinct from the people at Sainsbury’s or Tesco. Most products at Waitrose were highly priced, and I often thought what pleasure these people got out of buying things from there even as the same thing is available at a ‘proletarian’ supermarket at a much cheaper rate. But Waitrose being Waitrose, they often reduced items to clear at least a week before expiry, while Sainsbury’s or Tesco did it only a few hours in advance.

The street did give me its fair share of surprises every now and then. There was an antiques shop on the road and the first time I went there was when they were about to wind up their business. I was surprised to find posters of Bollywood films from the 1950s and the 1960s – some neatly stacked on the floor and some put up on the walls. When I questioned the old man who owned the shop, he gave me a brief lecture on Bollywood appreciation. According to him, the most remarkable thing in those posters was that the tile was written in Hindi, Urdu and English. As if that was not enough, the rest of the doses in Bollywood appreciation were given to me by my Chinese and Korean flatmates, who chided me for not being abreast with the latest trends in Bollywood as they were. They never quite understood how I, despite being fluent in Hindi, could not grasp the genius in these films that they understood from the dubbed Chinese.

II: Sunny sides of the street

Despite being lined by all fancy supermarkets that Britain boasts of, and despite being sparsely populated compared to, let’s say, Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, for some reason Holloway Road had a certain eeriness and tension about it. There was little else to it than selling and all shops closed down by 5 pm. Most people I saw on the street were dressed in a most bizarre fashion. Women were usually straight-faced, plastered with make-up and smelled of strong perfume when they crossed you. One portion of the street had shops clearly owned by people of a Somali origin and at evening you could see them creating a ruckus in that area. My feet quickened themselves automatically while going through that portion of the street, even though I must admit not one of them ever touched me or struck a conversation with me. Around Waitrose you mostly saw very old people walking very slowly somehow managing their shopping caddies. My streets in India bore a depressed look as well, but because of the bad infrastructure and planning, not because of the people. Despite the heat and dust, the streets I knew in India had a certain relaxed and genuine air about them, almost hangover of an old bazaar long gone. The people you see out on the streets in India are essentially there because they are bored, not really because they have to buy anything.

Compared to Holloway Road, other streets like Oxford St, Tottenham Court Road and Euston Road were much more crowded and hence more quick-paced. None of the people there looked as if they belonged there and in all probability came from all over the world to shop and leave: as if an eagle swooping down on a prey and taking off. Yet, it was on these streets that some people succeeded to carve their own niches on the footpath. They sat on the tables laid out by cafes, coolly sipping wine, completely oblivious to the traffic. Their own territory had been innocently and confidently marked by small banners bearing the logo of the restaurant. Unlike Delhi, where crowds keep on increasing as you move from the centre to the periphery of the city; London is the exact opposite: the centre is where the people are and the peripheries are near abandoned.

There was not a single day when some or the other portion at these busier streets was not cordoned off for construction, necessitating the traffic and pedestrians to flow around the closed-off area. Pedestrians involuntarily stepped on the street and drivers and riders did inch over the footpaths, but it was always in a manner more neater and safer than in a similar scenario in India. The crossing at Oxford St and Tottenham Court road, that eventually led to Charring Cross Road, always had street musicians performing loudly whose music when mixed with that coming out of shops and cars produced a cacophony that will be second only to Indian weddings. Thanks to the cacophony, I must have passed that crossing at least 365 times and never quite understood that twilight area of the street where one species of people and traffic changed into another.

Then there were other kinds of streets and avenues. Those branching out and paved with cobblestones, banked by equally spaced trees and lights, but at once meant to serve as a walkway and a car parking. Here, once again, I would find cafes stretched out and couples walking in embrace. Unlike India, where walking on the street you are bound to feel you are a part of a bigger mosaic, most western cities take pride in allowing you to be your own microcosm even when out in the public.

***

London seems impressive by the day, with elegant people dressed in business suits everywhere you saw. The traffic too is orderly. But come sunset, the city changes its colours faster than the sky and the reticence that had lent London a certain class by the day vanishes without an apology. The traffic becomes a little unruly, fast and dangerous. Strange looking people — wearing fluorescent clothes, hair dyed in the most bizarre colours, with not an inch of their skin free of jarring tattooes — surfaced after dark. They spoke more loudly than their counterparts by the day. Even though they surely spoke English, it sounded like a different tongue altogether. It seemed each time of the day had its own stipulated dialect. More often than not I was only to happy to be back in my student accommodation – mostly really late at night – surrounded comfortably by Chinese students engrossed in their remote-controlled cars.

But I managed to observe all this only when I started cycling to work, as opposed to taking the bus or the tube as I did earlier. If travelling in the bus or tube gave me but an urban cross-section, cycling gave me a vantage point that offered me an unfiltered view of the city, on my own terms, at my own pace. I could stare at people getting down on their knees to tie their shoelaces and getting their trousers dirty in the process, or the tall, confident kid who dropped his burger on his shirt or the frustrated man who has lost his way and is nearly screaming at his phone. By and by, I realised London was very ordinary. As ordinary as ordinary gets. Even as that made me more comfortable, the realisation that the West is not as perfect as it appears in the VISA offices does hit you hard.

An occasional ride in public transport offered its own sights. On the Piccadilly Line, I once saw a man asleep whose head kept going down and he kept jolting himself awake, with his left hand holding a bar above and the right clutching a rolled newspaper. If my memory serves me right, it was a free copy of The Evening Standard that one cannot miss. Each time his head fell, his grip would loosen and he’d tighten his grip just when the newspaper was about to fall off. When he got up to disembark at his stop, he happily left the newspaper at his seat as if to mark his seat for next morning!

III: Food like ours

Sounds strange, but I subconsciously and instinctively avoided places that rubbed the foreignness of the place in. Thus, I sought great comfort in lecture theatres. Once inside classrooms and laboratories, I used think that I could might as well be in a classroom in New Delhi. I remember approaching everything with a certain trepidation, not least food.

The food scene was obviously not the same as in India, so I had to think twice before buying anything, especially because of the exorbitant prices. The sound of a whistle anywhere while riding on the streets reminded me of the pressure cooker. It was so common in India for spices to be sold in the open, and customary for us to take a pinch in our hands and smell it before buying. Whatever respectable spices I found in London were all sealed and bottled, which meant I could not smell it. Nonetheless, food led me to some interesting adventures. I tried experimenting with all kinds of cuisines on offer in London: Mexican, Italian, Korean, Turkish etc., but I soon realised that when compared to Indian restaurants, they had very few vegetarian items on the menu. As a vegetarian, Whenever I placed an order at any of these restaurants, fancy by my standards, I often got a sparsely populated dish with food that I found tasteless. On many occasions I sprinkled chili flakes generously or asked the staff to make my dishes as spicy as they could. One of my friends remarked that years of eating Indian food had just numbed my taste-buds.

After much ado, it was wise for my pocket to stop pretending to be a global citizen and find myself at the mercy of Indian restaurants. At least £5-10 bought me enough food to fill my tummy up. The Indian YMCA and the Hare Krishna restaurant became frequent haunts for me. I was surprised to find that Indian food is actually quite popular in the UK and that many working-class people eat at Indian eateries (‘curry houses’) because they are cheaper than their Italian or Japanese counterparts. I also noticed another strange thing: most chain outlets had Indians and Bangladeshis as waiters, while Indian restaurants had white waiters.

Some British people at the Indian YMCA whom I became accustomed to admitted that another reason why they came there was they could eat with their hands so freely. When I introduced a Chinese friend (whose father was in the Chinese Communist Party, by the way) to a thali at the Hare Krishna restaurant in Soho, where the smell of food and incense was enough to drown the smell of urine at the square, he liked it so much he offered to pay the entire bill. By the end of my stay, I was so seasoned that when I saw an Indian restaurant at the ghost town of Kyleakin in the Isle of Skye that has a population of but a hundred people, I did not as much as raise an eyebrow.

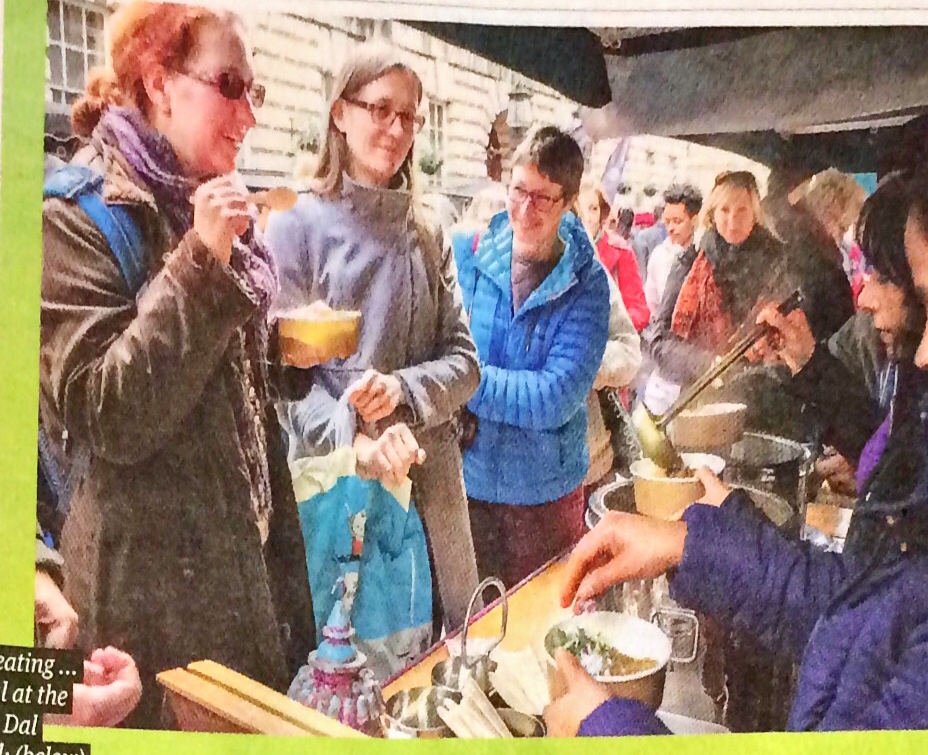

A scene at the British Dal Festival (The Guardian)

IV: Strangers in a strange land

But it was in interacting with the locals, or those who had spent some time in the UK that I really felt nervous. Before I had left India, I had read at least a dozen articles on how to conduct oneself in Britain. One of the teachings was not to ask anyone for directions. For the first few months I was there, I was constantly in a stage where I was testing the waters with an outstretched toe. Nearly each sentence I spoke was polished with endless reruns in my head before I finally uttered it.

But soon I felt at ease in London when I realised nearly everyone is as lost as me. At first, I found Europeans asking me for directions and having limited knowledge of English. It was quite a revelation for me to realise that non-English speaking white people, who otherwise gel in the crowd, were perhaps in direr straits than I. Then, I was pleasantly surprised when I found even British people (most likely not from London) asking me for directions – or even what time it was!

Here’s a funny thing though: it took some while for me to realise that nobody in Britain any longer says ‘beg your pardon?’ and they have taken to the American ‘what was that?’. I still remember the first time someone said ‘what was that?’ and me not understanding that he merely wanted me to repeat what I had said. Even I dropped the beg-your-pardon when I realised it is antiquated. Unable to bring myself to say ‘what was that?’ I resorted to a ‘sorry?’.

The Indian and South Asian diaspora were remarkably different. Broadly speaking, I could identify two distinct varieties of the Indian diaspora: one that was only too willing to shed off their Indian skin and be more British than the British; and ones who tried to amalgamate but refused to leave their ‘Indianisms’ in terms of language and food. The former enjoyed adequate representation at my hostel, where Indians tried their best to let as much of the London glitz rub off them as possible, stopping short of buying milk at Harrods. Diwali, Holi, Independence Day or Republic Day — they were just excuses to get drunk. It were the latter I pitied the most — poor fish out of water.

I should note that most Indians in the UK come from at least the upper-middle-class in India. In India, they would speak in English, so that rickshaw-wallahs or taxi drivers would not understand them. In the UK, they would speak in Hindi so that the locals would not understand them. What was quite hilarious was that we referred to the British as ‘foreigners’ even when we were in Britain.

Then there were unexpected encounters. A lady who used to work at a SportsDirect store nearby looked every bit as if she belonged there and spoke with a distinct London accent. She surprised me one day when she suddenly started speaking in heavily accented Punjabi over a personal call, switching from English to Punjabi between the store walkie-talkie and the personal cellphone. One Indian student was born in Spain, and grew up fluent in Spanish and Hindi; but her English was wanting. Then there were times I would be returning at the dead of the night and stop at a traffic signal, with a motorcycle rider beside me. Clad tip to bottom, one couldn’t guess his ethnicity until suddenly he would start speaking in Hindi into the earphones he had snugged in his balaclava. Walking on busy streets, I would often mutter something nasty in Hindi over my phone, and someone would turn back and look at me with a smirk. Then, at SOAS, I often found students flaunting oriental clothes, and wished I had brought some from home.

IV: First realisations

My first trip outside London was one to Windsor Castle – on a bicycle. (I was actually headed for Oxford but took a wrong turn and ended up in Windsor: a story for another day). Google Maps told me to keep following the Regents Canal and I alternated between clean pavements and muddy banks of the canal. Where there were clean pavements, the water was clean, where the pavements were muddy, the water was awash with algae. There were boats everywhere, though. One boat even had the words ‘Comfortably Numb’ written over it. Funny how I used to jump at a pop-culture reference in India, while the same thing in the UK seemed really banal.

After five hours, I finally hit tarmac when I exited London and passed through many areas that depict the typical English countryside. It was a strange landscape: if I looked to my left, I saw a neatly arranged row of brown houses with not a soul in sight; if I looked right, I only saw a medium-sized field with a shock of trees. I could obliterate either from my view at choice. So these were the famous English dales that Bronte, Hardy, Stevenson and Gaskell waxed eloquent about. I had read so many stories based in these landscapes that seeing them in person was quite an experience.

Then I foolishly rode my bicycle on a motorway (I think it was the M40). Thankfully, by sunset, I was on a train to London, with my bicycle and I covered in mud. But the day had brought with it a sense of disillusionment as well. Not everything in the West was spic-and-span as I had thought, and the badly maintained areas had come as a shock. I was soon to realise that there were many areas within London that were like that.

But the countryside, or whatever I saw of it, was breathtakingly beautiful and well-deserved the mental abilities of English writers. That a boy sitting in faraway Delhi could appreciate it in literature stood testament to the great skill of those writers. When the sense of wonder wore off, it brought with it an acute realisation how these landscapes became immortal essentially because they found expression in English and were transmitted because of colonialism. There were many landscapes in India that were as, if not more, beautiful as the English countryside but had rarely been considered worthy of description by an Indian writer in English. If they did get expressed, it was in the many Indian vernacular languages that were rarely translated to English. Now that Indians had been speaking English for at least a hundred years and had been an independent country for seventy years, should not we have done justice to our own landscapes and allowed those texts to reach other countries? At any rate, most descriptions of Indian landscapes in English that I knew of came before Independence!

This realisation manifested itself again when, during my spare time, I re-read RL Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde after nearly ten years. Stevenson’s and his contemporaries’ descriptions of London are so accurate and relevant even after a century, although I wonder what Stevenson would make of London now. The Dr Jekyll waiting for a horse carriage at the King’s Cross station today would in all probability be smashed by a fast motorcycle. Again, I have to give credit to the skill of those writers and for having dealt with such universal human themes that anyone who could read decent English could relate to them, even someone in faraway India.

Indeed, no wonder these writers were introduced by the British when they were in India to mould the Indian mind to European culture and, by extension, civilisation. But as you read their works, you cannot but admit that these very writers never wrote with an Indian or even a French or German audience in mind. They wrote for a very Southern English audience, for an audience that lived in their own small world of nice shops that sold books and umbrellas and walking sticks. Ask any Indian well versed in English literature if he knows an English writer of Scottish or Welsh origin, and you’ll know what I mean.

Even if they did summon characters from other parts of the world (take Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines or Kipling’s Kim, for instance), it was with the intent to amuse – not inform – this very audience. When they did base some stories within Britain, like Treasure Island by Stevenson, they took people who spoke a rougher tongue with whom Londoners would probably never have to contend. Their descriptions of the ‘other people’ or of Englishmen they considered ‘other’ were largely to give tasters of these people and places to a people that were otherwise bored with their Encyclopaedia Britannica. How did generations of Indians enjoy it, unquestioningly, and never bothered to subject their own lands to this scrutiny, beats me. I cannot take a moral high ground here as I am guilty of the same thing.

Moreover, I have never seen anyone obsessing over English grammar and pronunciation the way Indians do, not even the British. I never saw a French, Greek, Spanish or Italian making fun of his countrymen for speaking bad English. After observing them, even I started speaking in Hindi where I could help it, despite many injunctions by non-resident Indians in the UK not to do so.

V: The rest is noise

Paul Simon, in his album Graceland, sang how ‘every generation throws a hero up the pop charts’. I understood the import of this line during my stay in London.

My musical upbringing in India had been mixed: I had classes in Western and, to a lesser extent, Hindustani classical music. And I grew up listening to a lot of Sixties’ and Seventies’ rock music, oftentimes at lunch with generous helpings of daal and roti. My adolescent mind could not get its eyes off the sleeves of Pink Floyd and Deep Purple records or photographs from Woodstock (1969) or Monterey (1967). I spent all my money buying CDs and vinyls incessantly even though I could have downloaded them for free.

Oxford Street had a massive His Master’s Voice (HMV) store, which I discovered a little late than I should have. What a haven it was. The albums I had dreamt of having in my collection and had only until then seen in books of documentaries of the Sixties were all there, at prices I could afford. But I no longer had a turntable or a home theatre system like I did in Delhi, so I refrained from buying them. It would have only made me feel worse. Besides, when, in the end, I pack up my bags and go back to India, I would be able to carry only so much. Still, when the departure-day arrived, I had bought nearly ten CDs. Cream’s Wheels of Fire and King Crimson’s debut album were two of them.

It did surprise me when I realised that very few people from my generation in the UK listened to this kind of music, or at least I did not meet many. Even if there were, they probably did not deem fit to assert their identity and got lost among the crowds who had other music tastes. When I went to concerts by Jeff Beck, The Moody Blues and Camel, all products of the Sixties, I was the only young-head bobbing up in a sea of grey-haired people. I was surprised how the posters of these giants were mechanically put up at these venues a few days before their performance and unceremoniously removed to make way for musicals or even hip-hop stars. I feel that in India, the mere release of Bollywood films every week witnesses more fanfare than this. True, concerts by these Sixties’ and Seventies’ legends get sold out really early, but so do those of current-day pop stars, and at much higher prices.

HMV, Waterstones and UCL Main Library had many books on the Sixties’ culture, over which I pored. They had a very sobering effect on my outlook of the Sixties’ and Seventies’ that had been built by reading liner notes of albums and the Rolling Stone magazine. I must have been naive if my walks through London, for the first time, made me aware of the in-your-face fashion and advertising industry that the beat culture had spawned. It was perhaps in part due to the relative obscenity prevalent in British print media, even in the mainstream broadsheets like The Guardian. Thankfully, compared to the West, there is far less explicitness in Indian media (though the same cannot be said in the alternative online news outlets that have come up recently).

It was not long before I encountered accounts of groupies from the Sixties’/Seventies’ who felt compelled to have ‘consensual’ sex with rock icons like Page and Clapton to advance their musical prospects. Many of these accounts appeared as news reports (as if the journalists who write these news reports were any better, by the way). It was obvious that the much-avowed ideals of sexual liberation that the Sixties’ professed had been just as, if not more, patriarchal as the setup that existed before and had, just like the previous setup, been squarely advantageous to men, especially those involved in the music business. Much wiser now, when I go back to the music, this attitude is evident and it is strange how it eluded me for nearly ten years.

Consider John Lennon, for whom ‘love was such an easy game to play’ in ‘Yesterday’ (1966). Or the sleeve of the debut-album by British supergroup Blind Faith, wherein the young pubescent 13-year-old girl was asked to pose nude and written-off with a paltry £40. Blind Faith were not the only ones who resorted to nudity for sales when creative juices refused to oblige them. Or consider the words of Deep Purple’s ‘Living Wreck’ (1970) and ‘Mary Long’ (1972). What kind of mentality produced the Muddy Waters’ classic ‘You Shook Me’ (covered by Led Zeppelin (1969) and The Jeff Beck group (1968)). Consider, for instance, ‘Brown Sugar’ by The Rolling Stones or ‘There She Goes’ by The Velvet Underground. The list goes on. Weren’t these products of post-liberation counter-culture just as guilty of objectification? It shows how mentalities and inherent psychologies remained unchanged, only that there was a new façade. It is even more hilarious when the West appears quick to point fingers at the East for being ‘repressive’, when what goes on under the guise of ‘liberation’ is also questionable to say the least.us

Even more ridiculous were the deaths of drug overdose that happened, most notably, to Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin and to countless other counterculture adherents. How I had looked at them as martyrs, when they were nothing but victims of themselves. How juvenile and puerile the burning and smashing of instruments by The Who now seems, at which I had gaped with an open mouth. Why has the West, that holds the values of rationality and reason in such high esteem, failed to admit that the social mores encouraged by the West in the Sixties’ were disastrous to say the least? And that their ideals at the root of much unhappiness their people are faced with? That the fashion industry worked just like their tobacco and alcohol industry.

For the first time did I realise that the 1960s/70s were not without its discontents and that, from the comfort of my drawing room in Delhi, I had managed to consume an extremely filtered version of it. A version, that fit with my Indian outlook and could be pulled out at will.

***

But all was not grey, and music did bring to me some interesting encounters. Once I was walking down Oxford Street wearing a t-shirt of The Who. A man, probably in his fifties approached me and, skipping all the niceties, asked me to list five songs by The Who. I did that but he was still not convinced and asked me to list ‘some not-so-famous ones’. It was only then he was satisfied, and told me that he just wanted to check if I wasn’t wearing a Who shirt without knowing who they are (no pun intended) because ‘a lot of people do that nowadays’. On just my second day in London, I was at a small, quaint music shop where I met a man with long, white locks, easily in his seventies, who told me how he loved Indian philosophy over the Western one. ‘Kant and Nietzsche are all very good, but Ramanujacharya is in a league of his own.’ When I simply shrugged my shoulders, he told me he ‘expected this reaction.’

Epilogue

But he was mighty right. Ironically, that one year in the UK was to bring me closer to Indian literature and philosophy than all those years I had spent in India. Maybe it was because of encountering people Westerners like that Ramanujacharya-afficianado who were equally, if not better versed, about our heritage than me. Or encountering priests at the Hare Krishna temple who were all non-Indians and knew more about Hinduism and temple etiquette than Indians, often leaving me red-faced.

It was time to go home and brush up my knowledge of those things I should have rightly and dutifully learnt. As for rock, my constitution was not ready to have it without generous helpings of sambhar.

Related: UK Factsheet

Leave A Comment